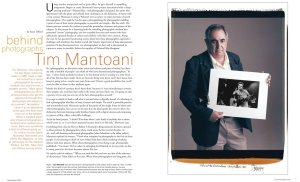

I am proud to say my Behind Photographs project is featured in the new issue of Communication Arts. It has been a little over two years that I have been working on this project. A special thanks to Anne Telford for the great article and six page spread. Pick up the March/April - 50th Anniversary Issue!

Blog

Tim Mantoani by Anne Telford

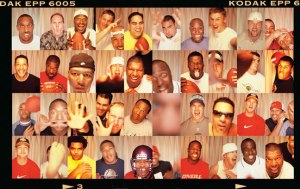

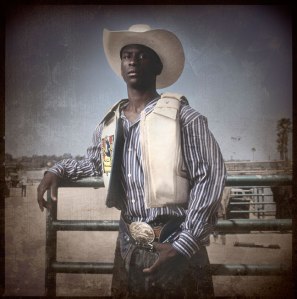

Tim Mantoani photographs an America you almost think you remember. He makes honest, simple pictures of everyday Americans. His is not so much an Avedon vision of America as a Cartier-Bresson one where through the small moments we all experience we are made to feel part of the larger community of man. Athletes celebrate their prowess and people react with their environment in uncontrived settings.

It’s apparent upon first entering Mantoani’s photo studio that he appreciates cultural artifacts. A rusted-out refrigerator holds stereo equipment and an old photo booth and soda machine lend a small-town 1950s air to the efficient and eclectic space near San Diego’s Little Italy neighborhood, conveniently located next to a camera store. If the vintage touches don’t instantly ground you, go into the kitchen, pick out your favorite candy from a variety of jars, and sit at the picnic table that serves as a conference table.

It’s also clear that Mantoani feels an emotional connection with the athletes he has photographed since the age of 21. He took his first photographs on a school field trip. He started out at U.C. Santa Cruz but transferred to Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara, his sophomore year, when he realized he really wanted to be a photographer.

As a child he had an Instamatic 110 with a flip flash and relished the opportunity at holidays to use his grandmother’s Polaroid SX-70. “The first time I looked through a 35 SLR camera I was a freshman in high school,” Mantoani relates. On a summer school trip to Washington, DC, and Pennsylvania he remembers standing on the steps above the Liberty Bell when one of the chaperones handed him his camera and asked him to take a picture. He can relate in excruciating detail what type of camera and lens it was, and the feeling he got when he framed his subject through the telephoto lens. That was Mantoani’s decisive moment. His neighbor in the San Francisco Bay Area town of San Carlos owned the local camera store and encouraged his father to buy Tim a second-hand camera. He still has that camera, and many more.

Mantoani comes from a family of collectors. His mom has collected Kewpie dolls since childhood and his dad, a hunter, collects duck decoys. Tim collects photographs—moments—which he captures with a variety of equipment. He muses about the sentimental value of cameras that one finds in thrift stores. “I think it’d be great if every time a photographer sells their camera, there’s a little journal that goes with it. I think of my Hasselblad... If this just showed up anonymously at the swap meet they would have no idea where this camera had been. What has this camera seen? What images has it recorded?” he wonders, ticking off the names of famous athletes he has captured over the years on his own equipment.

Photographer Dean Collins was his mentor. “He was the photographic educator,” Mantoani explains. Collins had an internship program, and Tim came to San Diego for seven weeks to work with him. He’d come down whenever he had a break, sweeping the studio and hanging out. Collins offered him a job as studio manager fresh out of school. Three years later Tim moved to associate photographer and after Collins retired, he and colleague Marshall Williams set up shop at their present location.

“The portraits that I’ve done have some staying power as far as a historical body of work that will live beyond me,” Mantoani says. “With the athletes I can say ‘I documented this group of people that were at the top of their sport in this period in history’ and that will have historical relevance versus shooting widgets in the studio for catalogs.”

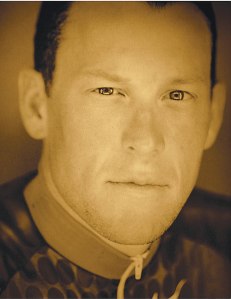

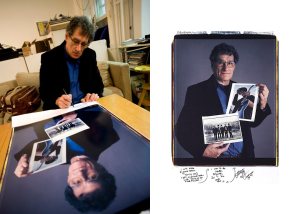

Mantoani’s latest project documents both a disappearing medium—Polaroids—and photography’s old guard, the guys who apprenticed with the greats and refined their techniques in the darkroom. At home with a view camera Mantoani is using a Polaroid 20 x 24-inch camera to make portraits of noted photographers. The angle he has hit upon, photographing the photographers holding a print of one of their iconic photographs, is powerful and simple, much like his work. His honest, simple pictures scratch the surface to reveal the personality of his subject: their character, their passion. In the process he is honoring both the vanishing photographic medium that pioneered “instant” photography, and the venerable lens men who have collectively captured decades of culture and celebrity with their own cameras. Legendary rock photographers Jim Marshall, Michael Zagaris and Dan Kramer have posed for Mantoani, along with Walter Iooss, Neil Liefer, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, Pete Turner, Eric Meola and Roberto Salas.

It’s not surprising that he gets to the heart of things. Nearly seven years ago, he developed a rare form of cancer. His son Lucas was born ten days after Tim’s surgery. No wonder that when asked what he likes to do in his spare time, he replies “Be a dad.”

“If you want to get all your stress out of the way at once, you buy a house, find out you have a tumor in your leg, close escrow on your house 3 days later, do 30 days of radiation, have your leg sawed in half, have a baby 10 days later and then do 6 months of chemotherapy,” Mantoani explains.

His mentor Collins’s death at 51, and his own brush with mortality, have informed his work in many ways. A surgeon telling him “get your affairs in order, you’re not going make it through this,” made him realize there was a limited time to make the Polaroid portrait project happen. He is creating a body of work that will be more relevant as time passes and the materials disappear.

“As a photographer, we document other artists and cultures and parts of society. But there are only a handful of people I can think of who have documented photographers,” he muses. “I don’t think anybody has done it in this format and it’s coming at a time when all of the film has been made, there are factories being torn down and I don’t know how long it’s going to be—maybe two years from now? There’s a good possibility that you’ll never be able to shoot in that medium again.

“Maybe this kind of a project hasn’t been done, because it’s very intimidating to contact these people, ask, and then they walk in the room and you think ‘OK, I’m going to take a picture of you and you are one of the best photographers around!’”

In an age where it’s hard to tell what is real and what is digitally altered, it’s refreshing to find a photographer who likes to keep it honest and simple. The result is powerful portraits and unvarnished craft. Mantoani speaks of the purity of the single frame in black-and-white photography. You can see in his eyes that that ideal sparks his creative drive; the dichotomy between shooting nearly limitless frames with a digital camera, with composing $75 pieces of film, offers a desirable challenge.

As for his latest project, “I think I’ll be done when I can’t think of anybody else to shoot who’ll come in, or I can’t shoot anymore because there’s no film left,” Mantoani says.